|

|

|

Paging Dr. Lean is brought to you by Patricia E. Moody, The Mill Girl at Blue Heron Journal. Submit your Paging Dr. Lean questions to tricia@patriciaemoody.com. |

In the Paging Dr. Lean series, Patricia E. Moody asks lean experts to answer your lean questions. This forum allows industry leaders to speak to the lean issues or questions you come across each day.

Dear Dr. Lean:

My company participates in a new product development consortium to exchange ideas and work through better new product approaches. Our business is growing and we think we need to figure out a radically different way to get new products out faster. We've looked at Don Clausing's concurrent engineering and now we're tossing around some ideas based on Allen Ward's new product development work, especially Mike Kennedy's Blue Book. We are in the medical device business, a great place to be.

But, I am wondering if our time-to-market problem is not just about new product design and development, and then launches. We've heard from customers informally that it takes four to five weeks for a typical customer to get one of our new high-volume items, three weeks if its expedited to us, but we know that actual production time is one shift. What we don't know is if we can change the gates in the health care value stream to speed up the whole cycle. In the end, all the customer really cares about is getting his equipment tomorrow.

What should we do? Where should we start?

Sincerely,

An Innovator

Dear Innovator:

It’s great to hear that you are involved in a new product development consortium to exchange ideas and work together to improve your product development systems. I encourage cross-company collaboration because consortiums can be effective in motivating change and “sharing best practices.”

However, bear in mind that although there are tremendous similarities in product development systems, there also are significant differences that make each approach unique. Be careful not to fall into the trap of simply implementing tools or techniques you find in the press. To effectively improve your development system you must first identify the problem.

Begin by asking the question, “What’s the problem we are trying to solve?” This can sound trite, but if you really dig deeply into this question as an organization it is not so simple. Continue to pursue this question until the organization can converge on one small place to start that would make a difference for your business. If this is a 15-minute conversation or even an hour-long discussion, you have not gone deep enough. To improve, you must first really understand and agree on the problem you want to go fix.

For example, an engineering department at a major gas company identified well uptime as a significant contributor to business success. When they really dug deep by repeatedly asking the question “What’s the problem?” they identified a sub-process related to funding approval as a key contributor to their engineering lead time. They decided to attack this issue and as a result nearly cut their lead time in half.

Superficially, every organization wants faster time-to-market. I hear this every time I speak with an organization. But what is behind the desire for improved time-to-market? I tend to think in terms of throughput. The contribution of the development system to the business is simply the delivery or output (throughput) of new products. According to Little’s Law, the throughput (TH) of a development system can be expressed mathematically as TH=WIP/CT, where WIP is the “work in process” and CT is the “cycle time” or “time-to-market.” Cycle Time (CT) or time-to-market is a function of utilization (U), variability (V) and process time (PT) of the various elements of the system.

Product development is very difficult to physically see. You can’t stand at your office door and see if the development line is “down” like you can in a factory. Focusing on throughput allows you to create mechanisms to ensure that product development is flowing. When you create flow, you can begin to attack disruptions to that flow and in turn improve your time-to-market.

Once you agree on the problem you want to go fix, such as well uptime in the example, don’t worry about fixing the whole system all at once. Attacking the financial approval process was a great place to start. Fixing it in turn uncovered additional system deficiencies to address. You already indicate that you don't know if you can change the gates in the health care value stream to speed up the whole cycle. Look at the problem from the customer’s point of view. Then, similarly in small steps look for things you can do to improve the utilization, variability or individual process time for elements in your development system since these are what control flow and your time-to-market.

Improving your development system will not happen overnight. It will take multiple cycles of identifying problems, implementing solutions, reflecting on the results and doing it again to change the system. Every improvement uncovers new opportunities.

When you agree on a specific problem you want to address, you may identify tools and techniques that can help you solve the problems, but don’t start with the tools. If you want to speed up the process, engage a competent coach or advisor you trust. I was very fortunate to be mentored by Dr. Allen Ward when I was learning. In my experience, it is best to find someone who “has been there” to point out what to look for and guide your problem solving. Keep in mind that lean product development is very different from lean in manufacturing, so be careful about trying to move lean manufacturing into product development. In the end, change is up to you — it’s most important to start somewhere small in a controlled manner.

Sincerely,

Dantar Oosterwal

Partner and President

Milwaukee Consulting Group

|

Dantar Oosterwal is a partner and president for the Milwaukee Consulting Group, which helps organizations create and implement improvement strategies. Prior to joining the Milwaukee Consulting Group, he was the vice president of continuous improvement and general management at Sara Lee, where he led worldwide implementation of continuous improvement efforts and drove adoption of lean methods across all aspects of the global business. Dantar also spent nine years with Harley-Davidson in a variety of roles including product development, cost management, engineering, procurement and continuous improvement.

Oosterwal has a passion for product development and the improvement of business systems. He has written a best-selling book, The Lean Machine, which presents the application of lean principles beyond the manufacturing environment and the associated cultural change necessary for knowledge workers. The Lean Machine describes the incredible impact lean principles can have on product development and chronicles the lean product development journey that Harley-Davidson travelled.

Oosterwal has a master’s degree in management from the Sloan School of Management at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and a bachelor of science degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Michigan.

Dear Innovator:

So, first off, you are already looking in the right places for benchmarks related to best practice approaches in lean product development. As you indicate, that does not seem to be your current challenge, given that it takes weeks to get a product that is likely made in just a few hours or so. Let’s cover your immediate problem and then go back to your new product development issue last.

One of the best places to start, my “prescription” in most problem analyses, is to map the process as it is today. Because this is really a true “value stream” from customer order through ultimate fulfillment and delivery to the customer/patient, drawing a value stream map is the best approach. You need to get the right team together to map the value stream. Ideally, it would be perfect to have the clinic that serves the patient involved. If they understand that their participation is going to improve the patient experience, they are usually glad to help. If the clinic is not available, at the very least, a patient or a knowledgeable and experienced sales person would work. You will also need the order-taking person, the insurance billing/processing person(s), production, shipping and perhaps a quality participant plus a couple of “process” outsiders to ask good questions, like, ”Why do you do it that way?”

If you are not well versed in value stream mapping (VSM) yourself, please find a practiced facilitator who has led at least a few dozen sessions. There are many folks with this capability in consulting, lean companies and education circles. Your facilitator or sensei should be objective to the problem/opportunity and be able to coordinate the needed data with the assembled team.

While not always followed, I would recommend that the entire team pretend that they are an example “order” and literally walk themselves through the entire process from the patient/customer to the final shipment and receipt. Because value stream mapping is really a learning exercise, it is imperative that the whole team experiences each step of the value chain as realistically as possible in the walk through of the order fulfillment process. Depending on your company’s complexity, this could be done in one hour or may take a half-day. Regardless, the learning in this process is invaluable.

Once the current state VSM has been assembled, the team should look at what activities are value-added (the customer would pay for them) and which are not. The team should brainstorm ways to eliminate the non-value-added (NVA) activities as much as possible. As a paradigm-changing goal, I also recommend that targets of at least 50 percent improvement should be the plan. Lead time should be then cut in half, the number of touches or steps should be half, etc. This 50 percent target forces improvement beyond the simply incremental level.

Simplification of the process and then trialing the new process should be the order of the day following the VSM session. Try the next process. How did it work? Any problems arise? If so, try something else until you achieve the 50 percent improvements. While this seems lofty, 50 percent is usually very attainable. Many VSM events that I have experienced have achieved up to 70 percent improvement overall.

Once the new process is piloted and proven, then the next step is to document the new standard work for the order fulfillment process and train everyone involved to follow it. It is imperative that everyone agrees to stay the course and stick with the new process for the time being while everyone adjusts to the new way. Avoid tinkering and drifting to ensure the new habits form.

To maintain control and sustainability of the new process, make sure that measures are put in place and tracked daily to prevent backsliding. One measure could be total lead time to ensure the gains are sustained. If not happening at least each month, after three to four months, the process should be revisited by the VSM team to ensure it is being sustained.

So now, let’s turn back to the improvement of the new product development process. Absolutely you should read both Allen Ward’s and Michael Kennedy’s books, and work to adopt their recommended approaches. Lean new product development tools, such as knowledge and set-based design, are good starts to an improved approach. Both books are excellent and touch on these tools as well as many more lean product development concepts.

Best wishes on your journey,

Jerry Wright

Senior Vice President of Lean and Enterprise Excellence

DJO Global

|

Jerry Wright is senior vice president of lean and enterprise excellence at DJO Global, an international medical device manufacturer with annual revenues of $1 billion. DJO has operations in 20 countries and sells products in more than 80 countries. Jerry works out of the company’s headquarters in Vista, CA. He joined DJO in 1997 and has held leadership positions in quality, engineering and operations. He has been one of the key change leaders that introduced lean thinking to transform DJO Global from a traditional batch-and-queue manufacturer to a world-class, lean enterprise.

During his tenure as the director of operations for the Vista facility, the operation was honored as one of the IndustryWeek Top Ten Best Plants in North America (2005). The Product Development Management Association (PDMA) awarded DJO Global the Outstanding Corporate Innovator Award that same year.

Jerry holds a bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering from Arizona State University and an MBA from the University of Phoenix. He is a licensed professional engineer in California and is a U.S. patent holder. Jerry is a Shingo Prize examiner, a former Baldrige Award examiner and past president of AME’s West Region. He is the lead instructor for the Lean Enterprise certificate course at University of California, San Diego. For the past eight years, he has chaired the Southern California Lean Network, an association of more than 75 companies that share best practices in lean, operational excellence and continuous improvement.

Dear Innovator:

|

| Source: PRIOR, new product development audit methodology for the systematic Improvement of Product design, Investment decisions, Operations Effectiveness and Return on investment, DAK Consulting, with permission |

The problems you identify about time to market could be caused by a number of factors. Long lead times could be due to difficulties in planning new products into an already full manufacturing schedule. It could also indicate that the science around your new product is not proven, so it is taking time to debug the new products and processes. The delivery of new products to customers is where symptoms of new product development (NPD) system weaknesses are made visible, and this could be the tip of the iceberg.

Back in 1990, the FDA reported that more than 40 percent of product recalls over a six-year period were due to weaknesses that could have been dealt with during the design process.

The fact that you can’t identify the causes of the extended time-to-market is an indication that your NPD systems are not as good as they need to be.

New product development is an evolutionary and often iterative process of learning and discovery. This is true not just of technical issues. Customers do not always know what they want, so developing something they can’t live without can be a frustrating and time-consuming process. Even when you do have a winning idea, the route to market can be equally frustrating. To paraphrase Thomas Edison, (NPD) genius is 1 percent creativity and 99 percent perspiration.

The foundation of effective new product development is good "knowledge flow" across commercial, operations and technical functions. Slick/lean processes to review and capture lessons learned at key stage gates will help you to gain a priceless insight into what customers really want and a route to trying out new ideas quickly with minimal effort.

Below are some ideas to help you to systematically improve your organization’s ability to generate innovative ideas that customers want that are easy to get to market and have some technical magic that is difficult to copy/patentable.

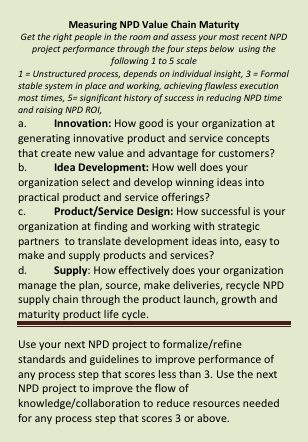

Start by assessing your organization’s NPD capability against the criteria shown in the box (measuring NPD value chain maturity). Involve representatives from commercial/customer-facing, operations and technical functions.

They should base their assessment on the evidence set out in the audit standards table below. These standards have been developed to identify areas of strengths and weakness in the processes, which coordinate knowledge and decision, flows across the three NPD process steps.

- Design performance management: The process of comparison of options against standards to guide design decisions, tease out latent weaknesses and develop the organization capability to deliver ROI goals.

- Specification life cycle cost (LCC) management: The process of selecting and refining winning ideas and translating them into low LCC, high-value products and service offerings.

- Project and risk management: The process of planning, organization and control of resources at each stage to deliver flawless operation from day one and ROI.

The table below sets out evidence-based audit criteria to help you assess capability at each step.

|

NPD Step |

NPD Step Audit Criteria |

||

|

Design Performance Management |

Specification LCC Management |

Project and Risk Management |

|

|

1. Innovation |

Has the preferred concept been selected through the evaluation of options against commercial, operational and technical design standards/expectations? |

Has the concept specification been refined based on an assessment of life cycle costs against best case/worst case scenarios? |

Are knowledge gaps identified? Has a route map and resources/strategic partners been identified to translate the concept into a robust product/service idea? |

|

2. Idea development |

Has the preferred product/service idea been developed from an evaluation of a short list of options and refined to improve project value? |

Is the specification for the preferred approach based on an understanding of design module criticality and an objective assessment against formal equipment management design standards? |

Is there a realistic and achievable plan and identified critical path supported by defined quality milestones and exit criteria? Are resources able to deliver those quality plan outcomes? |

|

3. Product/ service design |

Has the preferred approach been developed to reduce life cycle costs? |

Has the specification development included activities to tease out latent design weaknesses, improve value chain flow, reduce human error risks, process variability and sources of quality defects? |

Is there a clear understanding of what is needed to achieve flawless operation from operations day one? Do selected partners demonstrate their support for this goal? |

|

4. Supply |

Is there a clear operational optimisation route map in place? Have design standards been updated to take account of lessons learned? |

Are operations standardised? Is technical documentation up to date? Have accountabilities and priorities been set for commercial, operational and technical NPD optimisation? |

Have project targets been delivered? Are project closeout processes completed including lessons learned review? |

Source: PRIOR; New product development audit methodology for the systematic improvement of product design, investment decisions, operations effectiveness and return on investment, DAK Consulting, with permission.

To score a 3 in the NPD value chain assessment, systems and processes to deliver the evidence set out in the table above should be formalized and part of the routine (just the way we do things around here).

Don't award yourself more than a 3 unless you have formal, measurable processes in place and working. A score of 4 is for those who can demonstrate at least one to two years of measurable improvement in ROI for at least two NPD areas.

Use your next NPD project to

- Formalize processes for any step that scores less than 3.

- Reduce resources needed for any step that scores 3 or above.

Treat each NPD project as a stepping-stone to ratchet up the effectiveness of your NPD value chain. A hidden gem in the TPM toolbox, known as “early management” or “early equipment management,” sets out this road map very well. I recommend that you make this a part of your organization's NPD Lean improvement road map.

Sincerely,

Dennis McCarthy

Director

DAK Consulting

|

McCarthy and the team at DAK Consulting help organizations deliver year-to-year improvement in performance by developing internal capabilities, systems and processes. This includes the application of early management to NPD and capital projects for well-known and award-winning organizations, including 3M, Rolls Royce, BP, Premier Foods, Swedwood (IKEA), Heineken and Johnson Matthey.

He is the author of two books on continuous improvement. The most recent, Lean TPM, A Blueprint for Change, published by Butterworth Heinemann, sets out how the combination of lean and TPM create a practical road map to industry-leading performance.