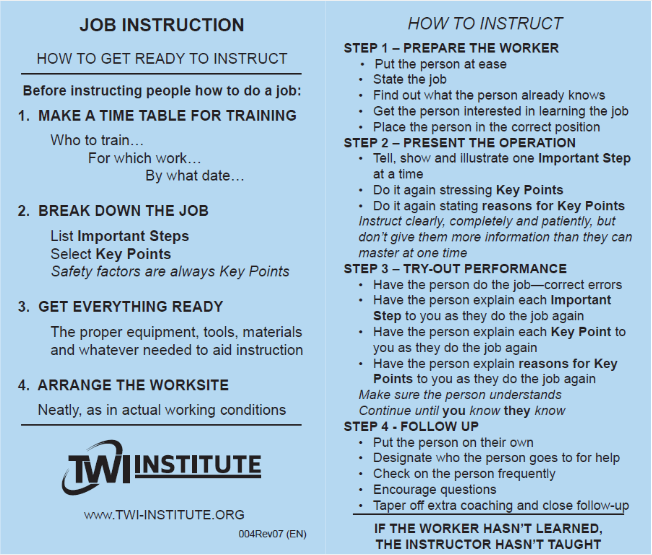

The Job Instruction card includes reminders that help instructors follow the TWI training guidelines.

“If the learner hasn’t learned, the instructor hasn’t taught.”

This phrase is printed prominently on the little blue card that summarizes Training Within Industry-Job Instruction (TWI-JI), the methodology that became a foundational piece of training at Toyota in the 1950s and has recently regained popularity within the lean community. I knew nothing about TWI-JI a few years ago when a rapidly growing manufacturer asked me to implement it to strengthen frontline training, but this phrase told me that the methodology was promising.

A few years before that, I had learned to practice lean by practicing Toyota Kata, where a coach takes responsibility for helping their learner develop the subconscious ability to think scientifically in daily work. So, I loved that TWI-JI asked trainers to take responsibility for their trainees’ growth.

It would take me almost a year to realize that this wasn’t just a nice philosophical catchphrase, but a practical guideline with broad, concrete implications that fundamentally challenged my approach as a lean practitioner.

Awareness is not enough

After about a month working on my TWI-JI deployment, it was painfully apparent that I didn’t understand the JI methodology deeply enough to teach it myself. Learning that JI is typically taught by a certified instructor in a standardized 10-hour class, I decided to bring in an expert who could do it right.

I connected with Sue Janus, a fellow Kata geek who I recalled had also delivered lots of TWI training. When Sue ran the JI class for my first wave of trainers, I was blown away by the high quality of her training. The content was concise and compelling, the format was engaging, and her delivery was very polished yet skillfully adapted to her participants.

At the end of the class, the trainers were unanimously convinced of the potential for JI to make them better and excited to get started.

I firmly believed that the best training class can only create awareness of new concepts and methods, but can’t truly develop skills. We learn by doing. So in the weeks following the class, Sue returned to spend time with the trainers in their work areas, helping them correctly apply the JI methods to their jobs. Again, I was amazed by the rich teaching and was thrilled to see that trainers were soaking up the experience.

I felt like we had a great approach and expected that deploying JI to additional waves of trainers would be smooth sailing. However, the following months surprised me, as these talented trainers struggled to apply the JI methods on their own. They felt awkwardly rigid when using the techniques in training sessions, and their teaching felt bizarrely monotonous to their trainees. Trainers grew reluctant to work on their deployment assignments, and, as tasks slipped, I increasingly felt the need to push execution. Some trainers started blaming their trainees for not absorbing the simple standards, and one became so frustrated with the methods that he abandoned JI altogether.

Although I was technically still meeting my deployment goals, it was clear to me that I was failing to meet the underlying business need. Despite the seemly excellent (and expensive) training provided, I could see that these talented trainers hadn’t developed proficiency with JI—somehow, they just hadn’t progressed beyond initial awareness of these methods.

Habits are stronger than intention

Toyota Kata’s development model is built on the belief that developing new skills requires these five components.

Through my Kata practice, I’d come to see that unexpected failures like this—though not exactly desirable—are valuable opportunities to learn something important. So I reflected on what I had missed. How could such good training, with such smart and high-performing people, with such significant initial momentum, produce such poor results?

Eventually, it struck me that everyone who had been exposed to the JI methods was already an experienced trainer. So, I wasn’t merely asking them to learn some new training skills, but rather to replace their existing habits with a new set of different habits! Like many lean methods, JI is based on concepts that conflict with conventional workplace norms—so I was actually asking these trainers to do things that contradicted their ingrained habits.

Looking at it from this angle, it suddenly seemed foolish to think that a class and a few hours of practice would produce transformational and sustainable behavior change. It suddenly seemed predictable that, when faced with the task of independently applying JI to their training tasks, trainers would struggle. I had just failed to be insightful enough to make this prediction.

Running home to Kata

Asking around a bit within the TWI community, I learned that my experience was somewhat typical and that the answers weren’t clear. One authority advised me to follow my Kata training: focus on what I needed my JI deployment to achieve, and then iterate my process to produce those results.

Toyota Kata has a powerful deployment model built on the belief that developing new skills requires specific ingredients:

1. Purpose: Gaining the expertise seems personally important to the learner.

2. Practice Routines: The skill is broken into simple instructional drills.

3. Frequent Practice: The routines are practiced often enough that they become familiar, requiring less effort to follow correctly.

4. Coaching: A trusted authority is present to help the learner see and correct errors in technique.

5. Mastery: Efforts produce a sense of progress, compelling the learner to keep going.

I realized that the little blue JI card is a Kata (a practice routine meant to ingrain a subconscious ability) to impart the ability to effectively deliver fast, consistent, engaging job training. It struck me that maybe I could borrow Toyota Kata’s skill development approach, simply replacing its practice routines with the “JI Kata.”

This realization meant that I had two of the required ingredients since the trainers had readily accepted the purpose of learning JI—they were trying to help the organization grow to save many more lives with its breakthrough product. However, I wasn’t enabling frequent practice for the trainers, as I was essentially turning them loose after their initial exposure. I wasn’t providing them with consistent, highly corrective coaching to correct the inevitable errors and deepen understanding as they faced inevitable obstacles when applying JI to different jobs and trainees. And I wasn’t helping them experience the feeling that their hard work was yielding results.

Suddenly, the mantra “if the learner hasn’t learned, the instructor hasn’t taught” felt like a personal indictment of my approach. These trainers were trying hard to learn JI and failing, and this was my fault. This reflection drove me to commit to building the skill development program that I owed to them and the business.

A new way to teach old tools

Following this decision, I worked with a couple of like-minded colleagues and consultants to build a JI deployment approach informed by Toyota Kata’s paradigm, including all of the ingredients necessary for skill growth. A year later, we had an effective process for taking someone interested in JI and equipping them with the skills and knowledge to apply its methods effectively.

We found that that a process along the following lines seemed to do the trick:

1. Recruiting: Look for people who want to learn and are willing to struggle through the process, taking coaching feedback, owning mistakes, adapting and trying again. Pushing training on people who don’t value it is a losing proposition.

2. Awareness training: Help people gain the basic awareness that they need to be ready to practice. Make sure that the purpose, practice routines and training approach are clear. (The standardized 10-hour JI class fits here.) Asking people to apply concepts or methods that they don’t understand, or that don’t feel important to them, is a losing proposition.

3. Initial practice: Get people comfortable with the practice routines in a safe environment, where the instructional drills are straightforward and mistakes don’t hurt. Provide intensive coaching oversight that can halt the exercise to highlight and correct errors before they become bad habits. Give time for trust to start growing between the coach and learner. Continue repetitions until the learner is ready for more complexity. Asking people to go practice when you don’t have coaching capacity to support them is a losing proposition.

4. Advanced practice: Shift practice to situations that are less straightforward, with higher stakes and more significant purpose. Taper down coaching slightly to let the learner struggle more, but not so much that they flounder. Ensure that the learner’s plan is clear before each rep, with the coach driving reflection and adjustment following each rep. Deepen trust between coach and learner. Continue practice cycles until the learner shows self-efficacy, with the desired depth of skill and mindset. Asking people to apply concepts or methods in new situations without a trusted coach helping them learn as they go is a losing proposition.

If we’re not growing people, what are we doing?

Somewhere in my earlier research into how to deploy JI, I had come across the following warning from Jeff Liker and David Meier’s in their book “Toyota Talent”:

“If your motivation is simply to do a better job of training because it will reduce problems and help the company, your outcome will not likely match Toyota’s. … Do it because you genuinely care about people and are committed to the effort required to help them achieve their highest potential.”

This passage haunted me because I knew that I was indeed after business results and didn’t know how to put people development first (outside of deploying Toyota Kata). By the time I handed-off my JI program, not only had I achieved the process gains that the business needed, but I had watched people grow dramatically— not just in their JI skills but in their sense of self-efficacy. Many seemed to carry themselves differently at work, with several earning significant promotions in the growing business. My JI work was far from perfect—its success and struggles uncovered many other weaknesses in my abilities and organizational obstacles to impact and sustainability—but I’m no longer troubled by this quote.

Today, I believe that the lessons learned in my JI deployment have much broader implications for lean practitioners. For decades, the lean movement has struggled to achieve and sustain the transformational impact that it seeks. Maybe the familiar old tools and concepts could have vibrant new life if leaders, managers and lean practitioners could see and embrace the practical implications to their own approach raised by the caution point on the little blue card: “If the learner hasn’t learned, the instructor hasn’t taught.”

Tyson Ortiz is a Boston-based performance improvement consultant. This article appears in the Summer issue of Target magazine. For more information about TWI, visit www.twi-institute.com. For more resources on Toyota Kata, visit the AME Kata Resources page.